The history of soccer scarves begins here. Behold, the soccer scarf. The beauty of which lies in its simplicity.

Its value is multiplied ten-fold by its versatility.

And its authenticity is certified in its organic growth, having become ubiquitous in a truly global game.

A textile of contradiction, it is a relic of football’s formative era, all while exhibiting an eternal youth to fans of all levels of investment in their team, for generation upon generation. The history of supporters’ scarves is about a cottage industry gone crazy and a modest swath of knitwear that is constantly adapting yet its essence remains unchanged.

Where would we be without our soccer scarves, anyway? Certainly, the stadium atmosphere would be relatively inert and drab. Fortunately for multitudes of impassioned patrons this cloth equivalent of the soft Swiss Army pocketknife can seemingly do it all: provide warmth or shade; tribal membership or individuality; static signage or flamboyant action.

What began as a finely woven accessory to ancient Egyptian queens had become a woolen staple of the working class by the mid-19th Century, when a sport whose seeds were sown in Britain was rapidly being exported around the world. The scarf has now followed suit.

Just Add Color

It’s impossible to answer who donned the first supporters scarf, contends National Football Museum collections officer Peter Holme. However, scarves were unquestionably among the first articles created to express support of one’s favorite club.

Shortly after teams began wearing “shirts of a fixed color, there were occasions – for example, at big games, such as cup finals – when the fans wanted to show their support,” Holme reports. “At first colored ‘favors’ (ribbons) were worn. Then, into the 1900s, we start to see rosettes, painted rattles, and colored hats or clothes.”

Sure enough, an examination of online photo and video archives finds, at first, only assorted shades of grey. In the early 20th century, spectators were almost exclusively male, wearing what would be considered business attire a hundred years later: white-collared shirts with neckties; tweed jackets; long, dark overcoats. It was also the age of hats; rarely does a bare head appear.

A visual sweep of the terraces finds the working-class blokes in flat caps; next are straw hats and an occasional bowler. They might just as well be outfitted for the theatre or church services.

A film from a 1927 Wolverhampton-Arsenal clash depicts fans celebrating goals by waving white handkerchiefs. Photos from 1929 mark the arrival of the aforementioned rosettes, pinned to lapels.

Granny Did It

Finally, a sighting. A brief British Pathe´ 1934 clip from Arsenal’s FA Cup fourth-round tie versus Crystal Palace yields the first prize of the hunt: the bar scarf. Seconds into the silent film, as fans fill the Highbury terraces, a solitary figure, a man wearing the requisite dark overcoat and fedora, is seen with a scarf of rotating bands of color, most likely red and black. He wouldn’t be alone for long.

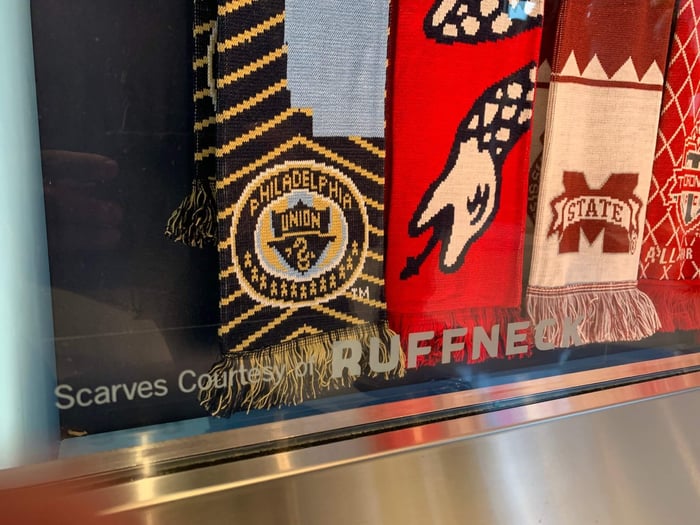

In 2018, Sunil Vidhani’s family will mark 50 years in the business of manufacturing custom soccer scarves, along with other accessories for fans. Their factory, which is a long time partner to Ruffneck Scarves, is located just north of Leicester, in Nottinghamshire, England. Vidhani knows of no existing documented history of the soccer scarf, but he’s certain that it all began with just such a scarf as seen at Arsenal.

Author and behaviorist Desmond Morris’s detailed exploration of the game and its traditions, The Soccer Tribe, noted that “scarves owe their origins to the need to keep warm on the freezing terraces of the damp and draughty British stadia in the dead of winter.”

“Generally, they were handmade scarves–granny scarves,” Vidhani contends. “They were literally hand-knit, with alternating bands of color and hand-stitched with fringe at either end.

“These were scarves knitted using needles, by mothers and grandmothers,” adds Vidhani. “That’s why they are referred to as ‘granny scarves.’”

British grannies must have burned some midnight oil in the coming years. Photographs from 1935-37 show an ever-increasing number of football fans draped in scarves. Sheffield Wednesday, Millwall and more Arsenal supporters are seen wearing bar scarves at the stadium and train depots. However, the boom time for scarfing Britain would have to wait until after World War II.

A Boy and His Scarf

It was on the eve of the war that Robin Chalmers was born on the outskirts of London. At the age of 8, the war ended and football once again in full force, Chalmers joined his father for the first time at nearby Stamford Bridge.

In those days, the Chelsea ground was mostly standing areas, hence a capacity of nearly 80,000. Being a young lad, he was awestruck by the atmosphere. The sheer size and roar of the supporters impressed young Chalmers and his brother, and it cemented their lifelong allegiance to the Blues.

“People didn’t wear bright colors,” Chalmers recalls. “It was mostly dark overcoats, hats and, of course, scarves. That’s the only way they could show their affiliation was a scarf.”

Shortly after that first match, Mrs. Chalmers surprised her boys by presenting them with homemade scarves of their own. “She knit it at night while I was asleep,” he shares, “and, all of a sudden, there it was.”

“It was blue and white stripes, nothing fancy like they have now,” he says. “It was quite long, about six feet, and about a foot wide, and it would go around my neck and down to at least my kneecaps. She made it quite thick, too. You could wrap it around in case it was cold.” Various other accounts of that era tell of granny scarves up to 10 feet in length.

Soon all of Chalmers’s classmates were wearing similar scarves, knit by their mothers. None of the clubs produced scarves, let alone operated shops in which to sell them.

Chalmers and his scarf were inseparable, especially on match days. Until, that is, a couple of years later and a home victory over the Gunners. Outside The Bridge, the two un-escorted boys encountered some older, bigger Arsenal fans. Robin and his brother had their prized possessions stolen, an act that embitters Chalmers to this day. Never fear, however. Soon his mother was back at work, knitting replacements.

“She was a dressmaker when she was young, so she was very quick at anything like that,” he notes. “She could really crank out the stuff.”

Chalmers never knotted the scarf. Rather, he wrapped it around his neck and, when Chelsea scored, he grabbed it and joined others in a celebratory mass swirling of the scarves. And there would be lots to celebrate, particularly when Chelsea won its first English championship, in 1955.

More Scarves, More Possibilities

Throughout the Fifties, scarves became a favorite Christmas gift throughout Britain. Some kids, wishing to make scarves appear more worn, would wash them multiple times, so the colors would bleed a bit.

Clearly, by the onset of the Sixties, the scarf had surpassed all other accoutrements in becoming emblematic of one’s tribe, one’s club.

The game was changing. More and more women and families were attending matches. As color photography became the norm, these bolts of color burst forth out of the grey in grounds throughout the land.

Poor Granny. And Mum. And Aunt Bertha. The demand for football scarves was far outstripping the capability of their caring fingers. At the same time, businesses saw an opportunity. Simple knitting machines that made onion sacks, said Vidhani, were modified to knit bar scarves. Same basic design, but it was now uniform in appearance and readily available to an increasing number of fans flocking to football matches.

“Not until the Sixties or Seventies did people say to themselves, ‘Hang on, we could actually make some money creating football scarves,’” claims Vidhani. At the time, the manufacturer would sell directly to fans. There were no club shops, per se. And at that stage, he adds, football clubs were much smaller operations and delighted just to see their colors displayed amongst the crowd.

Supporters were also discovering all the possibilities of scarves. Twirling was united by massive stretched scarf displays. Held above the head horizontally, when performed in unison it was becoming a bold spectacle, sometimes aimed at opposing supporters but more often as a visual accompaniment to the singing of You’ll Never Walk Alone.

“It is the display of proud supporters,” author Morris contends, “who feel an urge to pay homage to their heroes with a huge blanket of tribal colors.”

Walls of fan scarves became ever-present at Anfield, Upton Park, and, up north, Celtic Park.

Adds Morris: “(Scarves) have become much more than neck-warmers. Not only are they still worn in the comparative warmth of the spring cup finals and in August at the start of a new season, but there is an increasing tendency to wear them tied to the wrist rather than around the neck.”

Scarves worn on the wrist was also a telltale gauge of the fan’s commitment, indicating not only loyalty but a “hardness.” A “hard” fan, Morris wrote, “is one who is prepared to stand in the pouring rain or freezing cold” and will “join in the ritual battles with rival fans, skirmishes with police and various minor acts of hooliganism.”

Beyond Bars, Beyond Britain

In 1978, seeing an absence of anyone focusing on creating accessories for football fans, Sunil’s father, Kishan Vidhani founded his company. The initial project was producing terri-towel wristbands featuring club names. Intrigued, one of the big English clubs asked what more Vidhani could do.

He realized that if he modified an old jacquard sweater machine that knit patterns into the fabric, suddenly scarves could go far beyond bars. “He thought, ‘Why not knit the club crest into a scarf?’” says Sunil Vidhani. “We showed Manchester United and other clubs these scarves with their crest, and I remember very clearly United booked our factory for 25,000 scarves at a time. In fact, all the big clubs jumped on board. That’s when the football scarf business really boomed.”

During the early Eighties, supporter scarves became much more than just a British craze. Increasingly, scarves permeated Europe, and detailed designs were clearly visible in Spain and France. Germany, which was a few years behind in merchandise development, presented an even bigger opportunity with giant clubs like Bayern Munich, Borussia Dortmund, and Schalke.

Besides the jacquard knit and bar scarves came the first screen-printed, polyester scarves which could be quickly created to celebrate championships and cup finals. However, they were better suited for stretching and mounting on walls, not so much for winter warmth. Still, the possibilities for using scarves as a promotional vehicle seemed unlimited.

The scarf was becoming synonymous with soccer passion. The stretched scarf poses developed into the universal photo opp for new player and manager signings. And, sadly, mass displays of scarves also marked memorials for disasters such as Hillsborough and Bradford.

It was nearly impossible to satiate the fans’ voracious appetite for scarves. Because they were both affordable and available in an array of designs, scarves were always a hot commodity.

“We just couldn’t meet the demand,” admits Vidhani. “We were running 24 hours a day, producing 5000-7000 scarves per week. Around 1992 the demand became so immense that we had to look at new technology.” As a result, new computerized machines replaced the original jacquard knitters.

Approaching the Millennium, soccer scarf popularity was trending toward global. It was now vogue throughout western Europe and, with the fall of the Berlin Wall, flooding into the eastern reaches of the continent. Scarves were also appearing with increasing frequency in Africa and Japan. Still, there was room to grow.

North America: The New Frontier

Following the 1994 World Cup, soccer could once again claim a beachhead in America, and the advent of Major League Soccer afforded an avenue to create new traditions.

One of the emerging customs was supporters’ groups, both for clubs and country. They were organized and grown organically, and members were zealous in their backing. With their rhythmic clapping, elaborate signs, and incessant singing, they created a lively atmosphere for the fledgling league.

Then along came an expansion club that would fan the flames of that supporters’ passion and create a cauldron of color and energy throughout a stadium on the shores of Lake Ontario.

As the founding director of business operations for Toronto FC, Paul Beirne sought to create a genuine matchday experience for a truly cosmopolitan crowd, and one with close ties to European soccer. At the same time, TFC was looking to acknowledge the investment of its inaugural season ticket members.

Beirne wanted the gift to be authentic and soccer-centric, not some random, trashy trinket. He soon settled on a soccer scarf, and in so doing, Toronto set in motion the scarfing of North America in 2007.

“We wanted to achieve those authentic photographs you see, that imagery, that moment when everyone is standing and holding their scarves in the air,” remembers Beirne. “If we were to rely on people organically buying scarves, it might take years. We wanted to give it a kick start, and it’s that thought that caused us to attach the (first game’s) ticket to the scarf.”

Voila! Before the Reds had kicked a ball at BMO Field, Beirne and TFC had their moment. As 20,000 fans rose from their seats to greet their new team and sing the Canadian anthem, they proudly unfurled their new red scarves.

Later in the season, there was a counterintuitive response to the scarf displays. “You get that iconic moment when they are raising the scarves, but by game 5 or so, the other (non-season ticket holder) fans are seeing it, and so they want a scarf,” says Beirne. He notes that Toronto, despite already gifting 14,000, was the runaway MLS leader in scarf sales that season.

Two years later, made a second leap forward, now on the West Coast.

Seattle Sounders FC entered MLS and, borrowing from the TFC playbook, issued soccer scarves to all 22,000 season ticket members. Then, Beirne says, Seattle took scarfing to another level. There was a highly visible “Scarf Seattle” marketing campaign. A golden scarf was awarded to a deserving honoree and, prior to first kick, came the command to all fans for “Scarves Up!”

A Global Scarf Phenomena

By the time MLS turned 20 in 2016, the wearing, stretching, raising, and twirling of supporter scarves was rampant throughout the U.S. and Canada. According to MLS, scarves accounted for 10 percent of all licensed merchandise sales in 2016. Beirne said 10 years earlier, he scanned crowds and saw virtually no licensed scarves. And it was pervasive beyond MLS matches.

A soccer scarf is now commonplace at any game–internationals; women’s and lower-division pros; collegiate, high school, and youth clubs.

“I fully expected scarves to be part of the game here,” confirms Beirne, “but I did not expect it to do so with such speed and veracity. It’s gotten so completely huge. We brought it (scarves) to the forefront, but Seattle took it to another level. Seattle elevated it and became symbolic of something much more than just what you wear around your neck.”

Vidhani now produces a broad spectrum of sports scarves, including lightweight, polyester versions featuring high-definition, digital graphics. The market has exploded far beyond soccer and the game’s original bastions. Now a variety of sports at multiple levels are being supported by swathed fans on each continent (yes, he has shipped to Antarctica) as well as Caribbean nations. In addition, groups of all kinds–philanthropic, political, corporate–have opted to identify members using custom scarves.

While there will inevitably be future technological advancements to how scarves are created, the chief reasoning for fans wearing them may not.

The history of soccer scarves is set in place and can not be changed. “When groups go to a game, they are associating themselves with their fellow fans, and a scarf is used to show they are part of that tribe,” suggests Vidhani. “Since the beginning, people have lived in tribes, and now, rather than a shield or an emblem, the soccer scarf is a means to show which tribe you belong.”

Written by Frank MacDonald